SISSA, Scuola Internazionale Superiore di Studi Avanzati

Non basta osservare quali capacità sono alterate nei soggetti autistici, serve anche comprendere come ciascuna funzione interagisce con le altre.

L’attenzione condivisa, infatti, nei soggetti normali aiuterebbe la mimesi facciale (si tratta di due capacità base per l’interazione sociale umana), mentre negli autistici avverrebbe il contrario. Lo suggerisce un nuovo studio pubblicato su Autism Research.

L’empatia (la capacita di immedesimarsi e comprendere le emozioni degli altri) ha molte componenti, alcune sofisticate che coinvolgono processi di pensiero complessi, altre tanto basilari quanto essenziali. Fra queste ultime ci sono l’attenzione condivisa – la capacità che due, o più, individui hanno di porre attenzione allo stesso oggetto, e che viene avviata dal contatto visivo tra due persone – e la mimesi facciale – la tendenza a riprodurre sul proprio viso le espressioni emotive degli altri. Le persone affette da autismo hanno difficoltà con entrambe, ma secondo una nuova ricerca pubblicata su Autism Research, il segreto starebbe nell’interazione fra queste due funzioni.

L’empatia è una caratteristica umana fondamentale nelle relazioni sociali – spiega Sebastian Korb, ricercatore della Scuola Internazionale Superiore di Studi Avanzati (SISSA) di Trieste, fra gli autori della ricerca. – Secondo le teorie dell’embodied cognition (cognizione incorporata) per meglio capire l’espressione che vediamo sul viso di chi ci sta davanti riproduciamo la stessa espressione sul nostro viso.

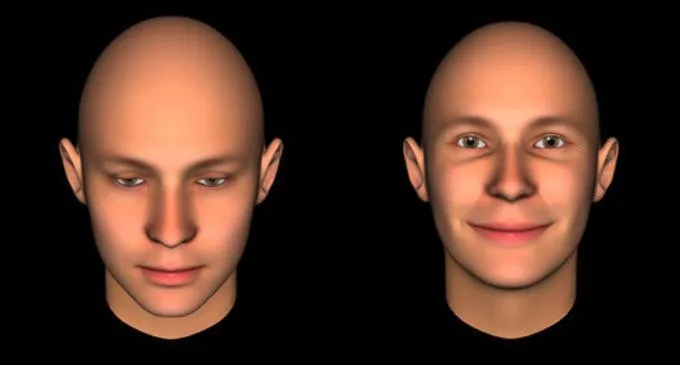

Questo non significa che per forza quando vediamo qualcuno sorridere dobbiamo sorridere a nostra volta, anche se a volte succede davvero. Più spesso però i muscoli facciali coinvolti nel sorriso si attivano, ma in maniera talmente lieve che il movimento non è visibile a occhio nudo.

La nota difficoltà delle persone autistiche nell’interpretare le emozioni degli altri potrebbe avere le sue radici proprio in una ridotta mimesi facciale, poiché molti studi hanno dimostrato che in questi soggetti questa funzione è deficitaria. Altri studi hanno mostrato che anche l’attenzione condivisa è intaccata negli autistici. Anche questa funzione ha un’enorme rilevanza nell’interazione sociale. Ciò nonostante, i deficit di mimesi facciale e di attenzione condivisa nell’autismo rimangono dibattuti e poco conosciuti. Per questo:

Noi crediamo che si debba porre molta attenzione all’interazione fra queste due capacità – spiega Korb – Nei nostri esperimenti infatti abbiamo osservato che nelle persone con tratti autistici più marcati, l’attenzione condivisa ‘disturbava’ la mimesi facciale, mentre nei soggetti normali la agevolava.

Una questione di interazione

Va sottolineato che i 62 soggetti che hanno partecipato all’esperimento non erano persone con una diagnosi di autismo. Invece, i ricercatori hanno utilizzato un questionario per misurare la tendenza all’autismo in persone normali. Infatti, è stato dimostrato che in ogni individuo si possono trovare tratti più o meno autistici, che però nella più parte dei casi sono lievi e quindi non portano a una diagnosi.

Quello che abbiamo osservato è che nelle condizioni con attenzione congiunta e dove l’avatar sorrideva, nei soggetti con tratti autistici più marcati i muscoli del sorriso si attivavano poco, mentre in quelli poco o per niente autistici la risposta espressiva era molto più amplificata – spiega Korb – Gli individui senza autismo tendono ad avere una risposta empatica (e una mimesi facciale) più forte con le persone con hanno avuto contatto visivo e stabilito un’attenzione condivisa. Ma se ci sono tendenze autistiche il contatto visivo al contrario può distrubare e diminuire la mimesi facciale.

Conclude Korb:

Per comprendere sia i meccanismi base di una buona interazione sociale, che i processi alterati alla base dell’autismo, è dunque importante non solo osservare quali funzioni sono danneggiate, ma anche come queste lavorino in concerto

La ricerca è stata svolta in collaborazione con l’Università di Reading, Regno Unito, (è stata coordinata dal Bhismadev Chakrabarti) e altri istituti di ricerca europei.

IMMAGINI: Avatar simili a quelli usati negli esperimenti. Crediti: Sebastian Korb

CONTATTI: Ufficio stampa: [email protected]

Tel: (+39) 040 3787644| (+39)366‐3677586 via Bonomea, 26534136 Trieste

Maggiori informazioni sulla SISSA

The gaze that hinders expression: autism and altered connections between eye contact and facial mimicry

It is not enough to observe what abilities are altered in autistic subjects, we also need to understand how each function interacts with the others. In fact, whereas in normal subjects joint attention appears to facilitate facial mimicry (both are skills relevant for human social interaction), the opposite holds true for autistic subjects. That is what a new study, just published in Autism Research, suggests.

Empathy – the ability to identify and understand other people’s emotions – has many components, some sophisticated and involving complex thought processes, others basic but essential nonetheless. The latter include joint attention – which is activated by direct eye contact between two or more individuals, and allows them to focus their attention on the same object; and facial mimicry – the tendency to reproduce on one’s own face the expressions of emotion seen in others. Subjects suffering from autism have difficulty with both these abilities, but according to a new study just published in Autism Research, it is also important to study how these two functions interact.

Empathy is an essential human trait in social relations – explains Sebastian Korb, a researcher at the International School for Advanced Studies (SISSA) in Trieste and one of the study authors – According to embodied cognition theories, to better understand the facial expression of the person in front of us we reproduce the same expression on our face.

This does not necessarily mean that if we see someone smiling we smile as well, even though this does happen sometimes. More often, however, the facial muscles involved in smiling are indeed activated, but so subtly that the movement is invisible to the naked eye.

The known difficulty autistic people have in interpreting other people’s emotions could stem from reduced facial mimicry, since many studies have demonstrated that this function is defective in these subjects. Other studies have shown that joint attention is also impaired in autism, and this is another function that has huge relevance for social interaction. Nevertheless, the impairments in facial mimicry and joint attention in autism remain controversial and poorly understood. For this reason:

We believe the interaction between these two abilities deserves plenty of attention – explains Korb – In our experiments, we saw that in persons with more pronounced autistic traits, joint attention tended to ‘disturb’ facial mimicry, whereas in normal subjects it facilitated it.

A question of interaction

It should be noted that the 62 subjects who took part in the experiment were not individuals with a clinical diagnosis of autism. Instead, researchers used a questionnaire measuring the autistic tendencies of normal persons. In fact, it has been demonstrated that everyone has more or less autistic traits, although in most cases these tend to be mild and therefore do not lead to a diagnosis.

During the trial, the subject’s facial mimicry was measured by facial electromyography (a method used for recording muscle activation).

What we observed is that in conditions of joint attention and where the avatar smiled, the subjects with more pronounced autistic traits tended to show less activation of the major smile muscle, whereas those with milder or no autistic traits showed a much more amplified expressive response – explains Korb – Individuals without autism tend to display a stronger empathic response (and facial mimicry) to persons with whom they have established eye contact and joint attention. However, if the subject has autistic tendencies then the eye contact can disturb and diminish facial mimicry.

Korb concludes:

In order to understand both the mechanisms underlying normal social interaction and the altered processes involved in autism, it is therefore important to observe not only which functions are impaired but also how these functions work together.

The study was carried out in collaboration with the University of Reading, United Kingdom (it was coordinated by Professor Bhismadev Chakrabarti) and other European research institutes.